人类肠道中有数以万亿计的微生物,构成了一个非常复杂的微生物群落,在维持人体健康方面发挥着至关重要的作用[1]。在生命早期,尤其是新生儿期,肠道菌群的定植及皮肤微生物的组成和变化在个体构建免疫系统、对抗过敏及感染中起到关键作用[2]。这一时期肠道菌群的失调可能会导致未来疾病的发生风险增高,例如哮喘[3]、肥胖[4]和炎症性肠病[5]等。以往认为,宫内环境为无菌环境;但越来越多的研究显示,胎儿在宫内暴露于一定的菌群。有研究显示健康人的胎盘[6]、羊水[7]、脐带血[8]可能也存在微生物,胎儿在宫内可能已经与微生物接触。新生儿肠道微生物可能来源于母亲的肠道、阴道、口腔、皮肤等部位的微生物[9]。新生儿出生后立即受到来自母亲和周围环境微生物的快速定植[10],新生儿肠道菌群的建立会受到分娩方式、胎龄、地理位置等因素[11]的影响。而目前的研究主要集中在新生儿肠道菌群的影响因素方面,关于胎儿肠道微生物的母婴传递的研究较少,还有待探索。关于新生儿肠道微生物建立的时间和来源尚不清楚。

分娩过程中,尤其是自然分娩的过程,新生儿皮肤从宫内环境暴露到微生物丰富的外部环境,可能是获取母亲菌群的重要途径之一。胎皮脂覆盖于胎儿皮肤表面[12]。由于皮肤菌群采样必须在胎儿娩出后及时完成,研究胎儿皮肤菌群有一定的难度,目前新生儿皮肤菌群研究不多。研究新生儿胎皮脂的菌群组成,有助于深入地了解新生儿皮肤微生物的定植。

本研究拟分析母亲孕晚期肠道菌群、阴道菌群和阴道自然分娩的配对新生儿胎粪菌群的相关性,以及新生儿皮肤菌群组成,探讨母婴菌群之间的垂直传递及菌群多样性和构成的异同。由于分娩方式影响着新生儿菌群的形成,本研究仅对阴道自然分娩的母亲和新生儿进行分析。

1 对象和方法

1.1 研究对象

本研究招募了2018年8月—11月于上海交通大学医学院附属新华医院完成产前检查和分娩的11例孕妇及其自然阴道分娩新生儿11对,采集孕妇孕晚期粪便样本、阴道拭子及其自然阴道分娩的新生儿胎粪样本。2018年12月招募于上海交通大学医学院附属国际和平妇幼保健院完成产前检查及分娩孕妇的自然阴道分娩新生儿14例,采集新生儿额部、腋窝、腹股沟的胎皮脂样本和胎粪样本。孕妇纳入标准:① 年龄20~45岁。② 单胎足月妊娠,阴道自然分娩。③ 汉族。排除标准:① 辅助生殖。② 母亲孕前BMI≥30 kg/m2。③ 母亲泌尿生殖道感染(如β链球菌感染、衣原体感染、支原体感染、细菌性阴道炎)。④ 孕期使用抗生素。⑤ 胎膜早破。⑥ 胎儿已知患有严重畸形。⑦ 母亲已知患有孕前糖尿病、依赖药物治疗的慢性高血压、先兆子痫、子痫,患免疫相关疾病或其他需要服用激素类药物治疗的疾病,如系统性红斑狼疮、类风湿性关节炎。⑧ 母亲患有严重肠道疾病或有胃肠道手术史。⑨ 母亲患有其他疾病,包括肿瘤、人类免疫缺陷病毒(HIV)阳性、梅毒、乙型肝炎、丙型肝炎、结核。

1.2 样本的采集

母亲孕晚期粪便样本及阴道分泌物的采集均在孕妇住院待产期间(分娩前1~2 d)采集。孕妇粪便样本采集:研究人员戴好灭菌手套,取孕妇排泄中后部深层的粪便,避免混入尿液或其他杂物;取约5 g粪便样本,放入灭菌冻存管中,拧紧管盖。孕妇阴道分泌物采集:研究人员将棉拭子插入阴道后穹窿处,轻柔沿阴道壁旋转5次,轻柔取出避免接触到阴道其他部位和外阴部以防污染。将拭子头部折断放入灭菌冻存管中,拧紧管盖。

新生儿胎粪样本采集:取新生儿出生24 h内首次排出的粪便样本。研究人员戴好灭菌手套,用无菌棉签从新生儿纸尿布表面挑取胎粪样本约2 g,将胎粪样本放入冻存管中,拧紧管盖。

新生儿胎皮脂样本采集:产科护士使用灭菌手套,在新生儿娩出5 min内,取新生儿额部、腋窝、腹股沟皮褶处的胎皮脂样本,避免拭子头部触碰到其他地方,将拭子头部折断放入配套灭菌管中,拧紧管盖。

所有样本采集后,均冰上转运至实验室,及时冻存于-80 ℃冰箱。

1.3 16S rRNA测序及分析

提取样本的DNA,使用Illumina测序将细菌16S rRNA基因的V3~V4区进行PCR扩增,使用Agencourt AMPure XP磁珠对PCR扩增产物进行纯化并溶于洗脱液,贴上标签,完成建库。使用Agilent 2100生物分析仪对文库的片段范围及浓度进行检测。检测合格的文库根据插入片段大小选择MiSeq进行测序。下机数据经过数据过滤,滤除低质量的测序片段(reads),剩余高质量的clean data方可用于后期分析;通过reads之间的重叠(overlap)关系将reads拼接成序列标签(tags);按照97%序列相似性聚类生成操作分类单元(operational taxonomic unit,OTU),然后通过OTU与数据库比对,对OTU进行物种注释;基于OTU和物种注释结果进行样品的后续分析。

1.4 统计学分析

所有微生物组数据的统计分析均在深圳华大基因微生物扩增子系统(

2 结果

2.1 研究对象一般特征

表1 11对母婴的临床特征

Tab 1

| Characteristic | Value | Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristic (n=11) | Weight gain in mid to late pregnancy/kg | 12.69±4.50 | |

| Age/year | 29.00±4.03 | Gestational diabetes mellitus/n(%) | 1(9.1) |

| Education level/n(%) | GBS positive/n(%) | 0(0) | |

| High school or below | 3(27.3) | Puerperal fever/n(%) | 0(0) |

| College or above | 8(72.7) | Infant characteristic (n=11) | |

| Parity/n(%) | Infant gender/n(%) | ||

| 0 | 8(72.7) | Girl | 4(36.4) |

| ≥1 | 3(27.3) | Boy | 7(63.6) |

| Antibiotics use during child delivery/n(%) | Weight for gestational age/n(%) | ||

| No | 8(72.7) | SGA | 2(18.2) |

| Yes | 3(27.3) | AGA | 8(72.7) |

| Early pregnancy BMI/n(%) | LGA | 1(9.1) | |

| <18.5 kg·m-2 | 0(0) | Entering NICU after birth/n(%) | |

| 18.5‒23.9 kg·m-2 | 8(72.7) | Yes | 1 (9.1) |

| 24.0‒27.9 kg·m-2 | 1(9.1) | No | 10(90.9) |

| ≥28 kg·m-2 | 2(18.2) | Gestational age at birth/week | 40.18±0.75 |

| Pre-delivery BMI/n(%) | Length/cm | 50.27±1.62 | |

| <18.5 kg·m-2 | 0(0) | Birth weight/g | 3 536.36±423.66 |

| 18.5‒23.9 kg·m-2 | 0(0) | Head circumference/cm | 34.55±1.21 |

| 24.0‒27.9 kg·m-2 | 6(54.5) | Birth BMI/(kg·m-2) | 13.96±1.15 |

| ≥28 kg·m-2 | 5(45.5) | Neonatal antibiotics use/n(%) | 0(0) |

表2 14名新生儿及其母亲的临床特征

Tab 2

| Characteristic | Value | Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristic (n=14) | Weight gain in mid to late pregnancy/kg | 11.09±9.63 | |

| Age/year | 30.43±2.90 | Gestational diabetes mellitus/n(%) | 1(7.1) |

| Education level/n(%) | GBS positive/n(%) | 0(0) | |

| High school or below | 3(21.4) | Puerperal fever/n(%) | 0(0) |

| College or above | 11(78.6) | Infant characteristic (n=14) | |

| Parity/n(%) | Infant gender/n(%) | ||

| 0 | 10(71.4) | Girl | 7(50.0) |

| ≥1 | 4(28.6) | Boy | 7(50.0) |

| Antibiotics use during child delivery/n(%) | Weight for gestational age/n(%) | ||

| No | 11(78.57) | SGA | 0(0) |

| Yes | 3(21.43) | AGA | 10(71.4) |

| Early pregnancy BMI/n(%) | LGA | 4(28.6) | |

| <18.5 kg·m-2 | 0(0) | Entering NICU after birth/n(%) | |

| 18.5‒23.9 kg·m-2 | 11(78.6) | Yes | 2(14.3) |

| 24.0‒27.9 kg·m-2 | 2(14.3) | No | 12(85.7) |

| ≥28 kg·m-2 | 1(7.1) | Gestational age at birth/week | 39.14±0.95 |

| Pre-delivery BMI/n(%) | Length/cm | 50.00±0.88 | |

| <18.5 kg·m-2 | 0(0) | Birth weight/g | 3 418.93±371.51 |

| 18.5‒23.9 kg·m-2 | 2(14.3) | Birth BMI/(kg·m-2) | 13.66±1.26 |

| 24.0‒27.9 kg·m-2 | 8(57.1) | Neonatal antibiotics use/n(%) | 0(0) |

| ≥28 kg·m-2 | 4(28.6) | - | - |

2.2 母亲孕晚期肠道菌群、阴道菌群、新生儿胎皮脂菌群及胎粪菌群的菌群多样性及比较

2.2.1 菌群α多样性比较

图1显示了母亲孕晚期肠道菌群、阴道菌群和新生儿胎粪菌群共有和各自特有的OTU数目(图1A),以及新生儿3个部位胎皮脂和胎粪菌群共有和各自特有的OTU数目(图1B)。母亲肠道菌群、阴道菌群和新生儿胎粪菌群OTU数分别有445、351、255个,其中161个OTU在三者中相同/重叠;此外,母亲肠道菌群和母亲阴道菌群有76个OTU相同,胎粪菌群和母亲肠道菌群有26个OTU相同,胎粪菌群和母亲阴道菌群有36个OTU相同。新生儿额部、腋窝和腹股沟胎皮脂菌群和胎粪菌群OTU数目分别为410、482、563、180,其中额部、腋窝和腹股沟3处胎皮脂菌群有260个OTU相同,3个部位胎皮脂和胎粪菌群有103个OTU相同。

图1

图1

不同样本OTU数量的Venn图

Note: A. Maternal gut microbiota, and vaginal microbiota in late-pregnancy and neonatal meconium microbiota from the 11 pairs of mothers and newborns. B. Neonatal vernix caseosa (at forehead, axilla, and inguinal crease) and meconium microbiota from the 14 newborns.

Fig 1

Venn diagrams of the OTU numbers from different samples

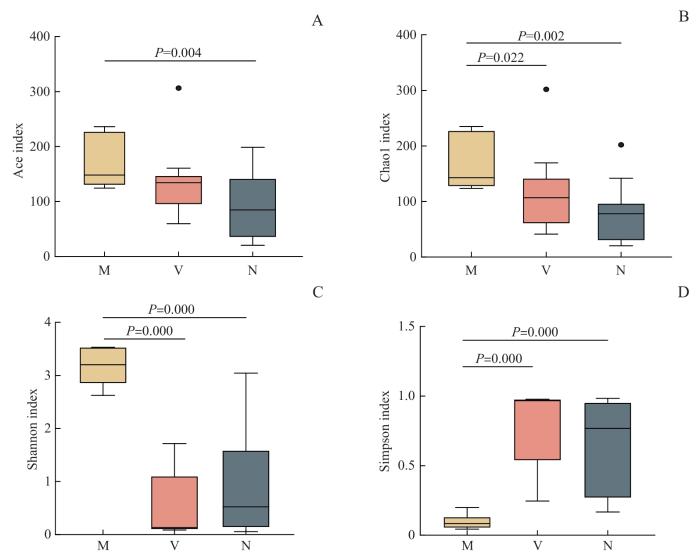

图2

图2

母亲孕晚期肠道菌群、阴道菌群和新生儿胎粪菌群Ace (A), Chao1 (B), Shannon (C)及Simpson (D)指数箱型图

Note: M—maternal gut microbiota; V—maternal vaginal microbiota; N—neonatal meconium microbiota.

Fig 2

Box plots of Ace (A), Chao1 (B), Shannon (C), and Simpson (D) indices of maternal gut microbiota and vaginal microbiota in late-pregnancy and neonatal meconium microbiota

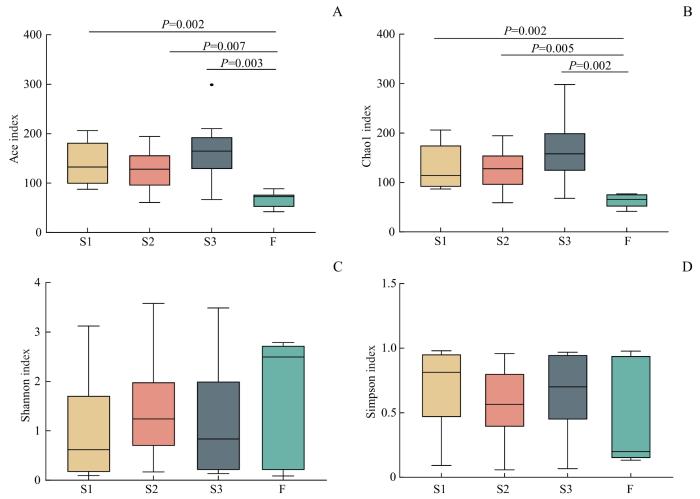

新生儿3个部位胎皮脂(额部、腋窝、腹股沟)菌群Ace指数和Chao1指数均显著高于胎粪菌群(均P<0.05,图3)。提示胎皮脂菌群的α多样性高于胎粪菌群。

图3

图3

新生儿胎皮脂菌群和胎粪菌群Ace (A), Chao1 (B), Shannon (C)及Simpson (D)指数箱型图

Note: S1—neonatal vernix caseosa at forehead; S2—neonatal vernix caseosa at axilla; S3—neonatal vernix caseosa at inguinal crease; F—neonatal meconium.

Fig 3

Box plots of Ace (A), Chao1 (B), Shannon (C), and Simpson (D) indices of microbiota in neonatal vernix caseosa and meconium

2.2.2 菌群β多样性比较

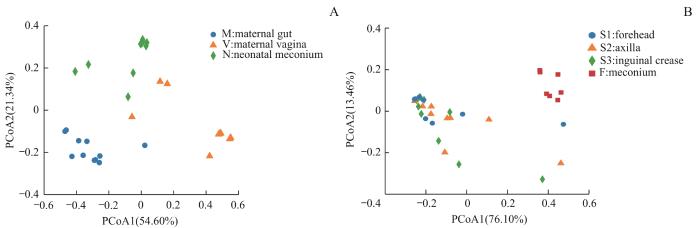

图4

图4

不同样本菌群β多样性PCoA分析

Note: A. Maternal gut microbiota and vaginal microbiota in late-pregnancy and neonatal meconium microbiota from the 11 pairs of mothers and newborns. B. Neonatal vernix caseosa (at forehead, axilla, and inguinal crease) and meconium microbiota from the 14 newborns.

Fig 4

PCoA analysis of β diversity of the microbiota from different samples

2.3 母亲肠道菌群、阴道菌群、新生儿胎皮脂菌群及胎粪菌群的菌群构成和比较

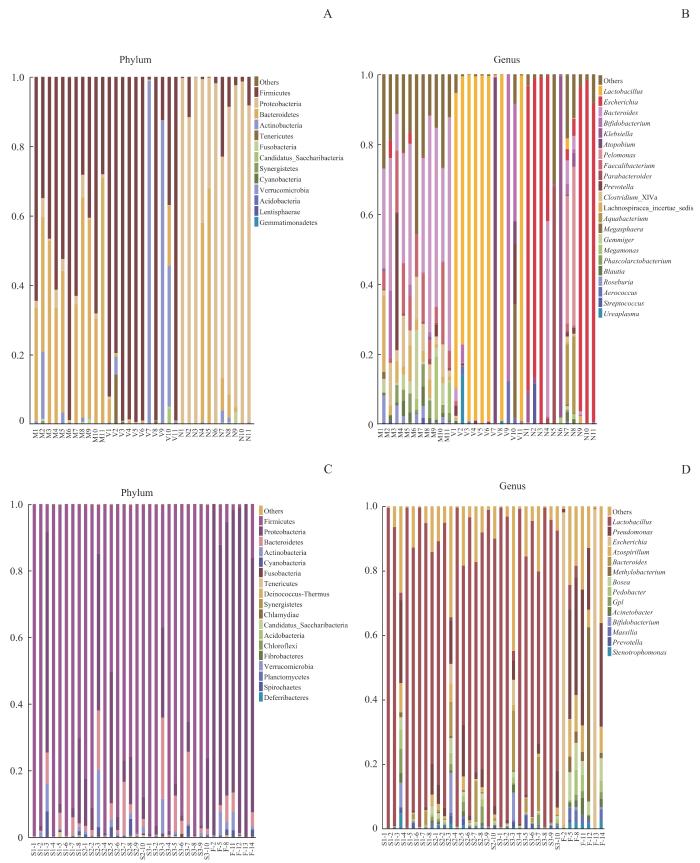

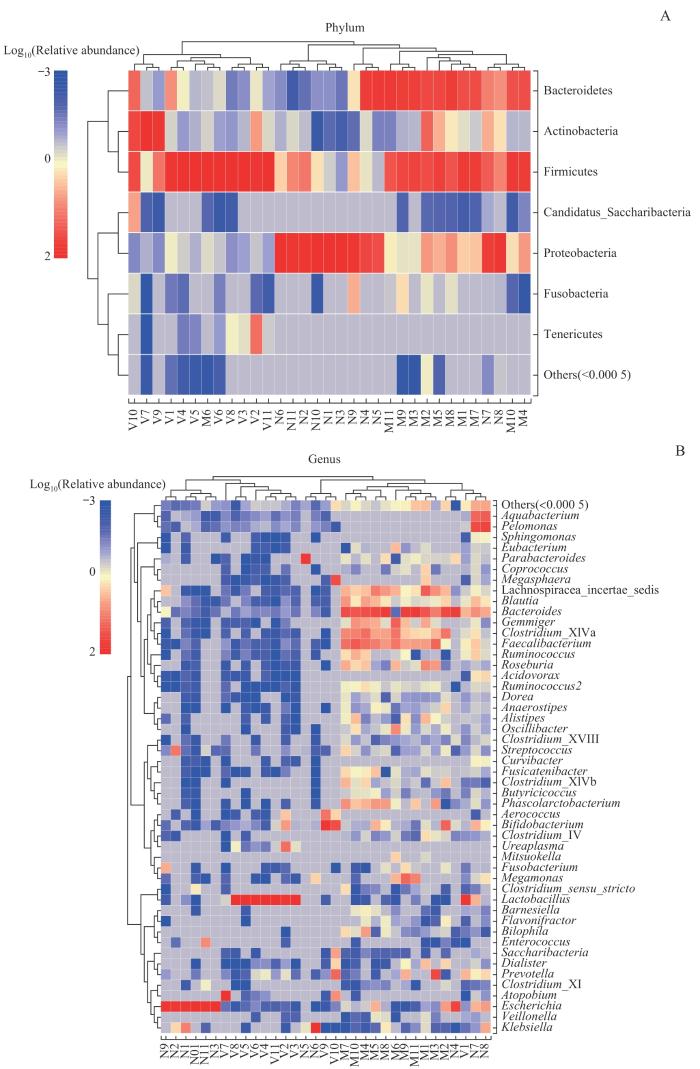

如图5A所示,在门水平,母亲肠道菌群以厚壁菌门(Firmicutes,52.76%)和拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes,41.67%)占主导,以下依次是变形菌门(Proteobacteria,2.76%)、放线菌门(Actinobacteria,2.40%)。母亲阴道菌群以厚壁菌门(74.36%)、放线菌门(21.25%)占主导,第三位是拟杆菌门(2.27%)。在11份样本中,新生儿胎粪菌群以变形菌门(81.11%)的相对丰度最高,为绝对优势菌门,以下依次是拟杆菌门(12.64%)、厚壁菌门(5.29%)。与之相似,另外7份新生儿胎粪菌群样本也以变形菌门(88.72%)为绝对优势菌门,相对丰度最高,以下依次是厚壁菌门(4.93%)、拟杆菌门(2.90%)。新生儿胎皮脂菌群以厚壁菌门(84.22%)占主导(图5C),以下依次是变形菌门(8.80%)、拟杆菌门(4.44%)。门水平上的菌群组成热图(图6A)显示厚壁菌门在母亲孕晚期阴道菌群和肠道菌群中占主导,在新生儿胎皮脂菌群中占比也较高。

图5

图5

不同样本菌群门和属水平物种相对丰度柱形图

Note: A/B. Maternal gut microbiota and vaginal microbiota in late-pregnancy and neonatal meconium microbiota from the 11 pairs of mothers and newborns at the levels of phylum (A) and genus (B). C/D. Neonatal vernix caseosa (at forehead, axilla, and inguinal crease) and meconium microbiota from the 14 newborns at the levels of phylum (C) and genus (D). M1‒M11: maternal gut microbiota; V1‒V11: maternal vaginal microbiota; N1‒N11: neonatal meconium microbiota; S1-1‒S1-8: neonatal vernix caseosa at forehead; S2-1‒S2-10: neonatal vernix caseosa at axilla; S3-1‒S3-10: neonatal vernix caseosa at inguinal crease; F-2, F-5, F-8, F-11‒F-14: neonatal meconium.

Fig 5

Histogram of relative species abundance at the phylum and genus levels in different samples

图6

图6

母亲孕晚期肠道菌群、阴道菌群、新生儿胎粪菌群门(A)和属(B)水平物种组成热图

Note: Due to the potential significant differences in relative abundance of species, sample clustering was affected. After multiplying the relative abundance by 100, a log transformation with a base of 10 was performed [y=lg(100x)]. If the relative abundance of species in the sample was 0, it would be replaced with the log value of half of the minimum value (≠0) of species abundance in all samples.

Fig 6

Species composition heatmaps at the level of phylum (A) and genus (B) in the maternal gut microbiota and maternal vaginal microbiota in late-pregnancy and neonatal meconium microbiota

属水平上,如图5B所示,母亲肠道菌群相对丰度排名前五的菌属为拟杆菌属(Bacteroides,35.42%)、栖粪杆菌属(Faecalibacteriu,10.12%)、梭状芽孢杆菌属(Clostridium XIVa,6.65%)、地位未定的毛螺菌科(Lachnospiracea incertae sedis,5.31%)和普氏菌属(Prevotella,4.09%)。母亲阴道菌群相对丰度排名前五的菌属分别是乳杆菌属(Lactobacillus,69.10%)、双歧杆菌属(Bifidobacterium,11.30%)、阿托波菌属(Atopobium,9.86%)、巨单胞菌属(Megamonas,2.64%)和普氏菌属(1.86%)。在11份样本中,新生儿胎粪菌群相对丰度排名前五的菌属为埃希菌属(Escherichia,55.21%)、克雷伯菌属(Klebsiella,10.38%)、暗单胞菌属(Pelomonas,7.42%)、副拟杆菌属(Parabacteroides,6.37%)和拟杆菌属(5.82%)。如图5D所示,新生儿胎皮脂菌群相对丰度排名前五的菌属分别是乳杆菌属(79.81%)、假单胞菌属(Pseudomonas,3.23%)、拟杆菌属(2.48%)、固氮螺菌属(Azospirillum,0.97%)和Gpl属(0.79%)。在7份胎粪样本中,埃希菌属(31.18%)相对丰度最高,与11份新生儿胎粪菌群结果一致,以下依次为假单胞菌属(22.82%)、甲基杆菌属(Methylobacterium,8.32%)、固氮螺菌属(6.23%)和博斯氏菌属(Bosea,4.5%)。属水平上的菌群组成热图(图6B)也同样显示,拟杆菌属在母亲肠道菌群中的相对丰度最高,乳杆菌属在母亲阴道菌群中的相对丰度最高,埃希菌属在新生儿胎粪菌群中的相对丰度最高。

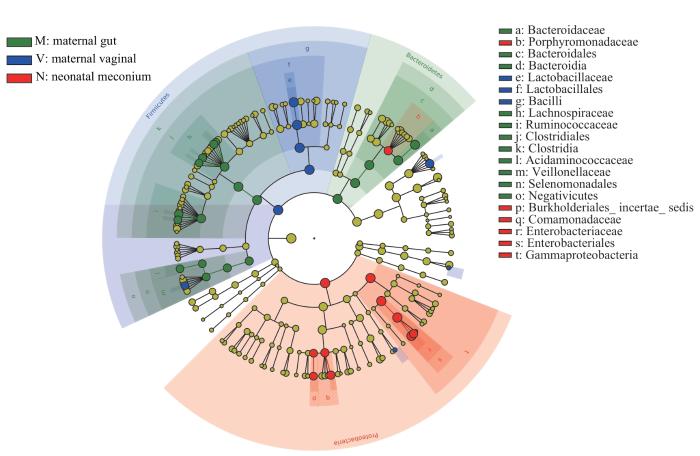

图7和图8为基于LDA值为4的进化分支图,进一步显示了微生物组成的差异。母亲肠道菌群中拟杆菌门和梭状芽孢杆菌纲(Clostridia)的相对丰度高。结合进化分支图(图7)可见,母亲肠道菌群中拟杆菌门的相对丰度高是由于拟杆菌科(Bacteroidaceae)的相对丰度高所致,梭状芽孢杆菌纲的相对丰度高是由于瘤胃球菌科(Ruminococcaceae)和毛螺菌科(Lachnospiraceae)的相对丰度高所致。母亲阴道菌群厚壁菌门相对丰度高是由于乳杆菌科(Lactobacillaceae)的相对丰度高。新生儿胎粪菌群中变形菌门的相对丰度高是由于肠杆菌科(Enterobacteriaceae)、丛毛单胞菌科(Comamonadaceae)和未定地位的伯克霍尔德氏菌目(Burkholderiales incertae sedis)的相对丰度高。

图7

图7

母亲孕晚期肠道菌群、阴道菌群和新生儿胎粪菌群LEfSe分析进化分支图

Note: Different colors in the figure represent different microbial communities. The yellow nodes represent microbial communities that do not play an important role in the 3 groups. The green nodes represent microbial communities that play an important role in the maternal gut microbiota. The blue nodes represent microbial communities that play an important role in the maternal vaginal microbiota. The red nodes represent microbial communities that play an important role in the neonatal meconium microbiota. From the inside out, each circle consists of species at the level of phylum, class, order, family, and genus.

Fig 7

LEfSe cladogram of analysis on the maternal gut microbiota, and vaginal microbiota in late-pregnancy and neonatal meconium microbiota

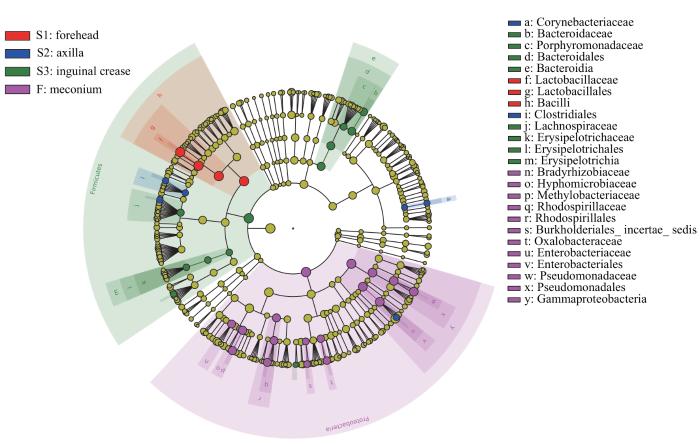

图8

图8

新生儿胎皮脂菌群和胎粪菌群LEfSe分析进化分支图

Note: The red nodes represent the microbial communities that play an important role in the neonatal vernix caseosa at forehead. The blue nodes represent the microbial communities that play an important role in the neonatal vernix caseosa at axilla. The green nodes represent the microbial communities that play an important role in the neonatal vernix caseosa at inguinal crease. The purple nodes represent the microbial communities that play an important role in neonatal meconium. From the inside out, each circle consists of species at the level of phylum, class, order, family, and genus.

Fig 8

LEfSe cladogram of analysis of the neonatal vernix caseosa microbiota and meconium microbiota

由图8可见,新生儿额部胎皮脂菌群芽孢杆菌纲(Bacilli)的相对丰度高主要是由于乳杆菌科的相对丰度高所致;腋窝胎皮脂菌群梭菌目(Clostridiales)、棒杆菌科(Corynebacteriaceae)的相对丰度高;腹股沟胎皮脂菌群厚壁菌门的相对丰度高是由于毛螺菌科、韦荣球菌科(Erysipelotrichaceae)等的相对丰度高所致,其拟杆菌纲(Bacteroidia)相对丰度高是由于拟杆菌科、卟啉单胞菌科(Porphyromonadaceae)相对丰度高所致。

2.4 母亲肠道菌群、阴道菌群、新生儿胎皮脂菌群及胎粪菌群的相似性

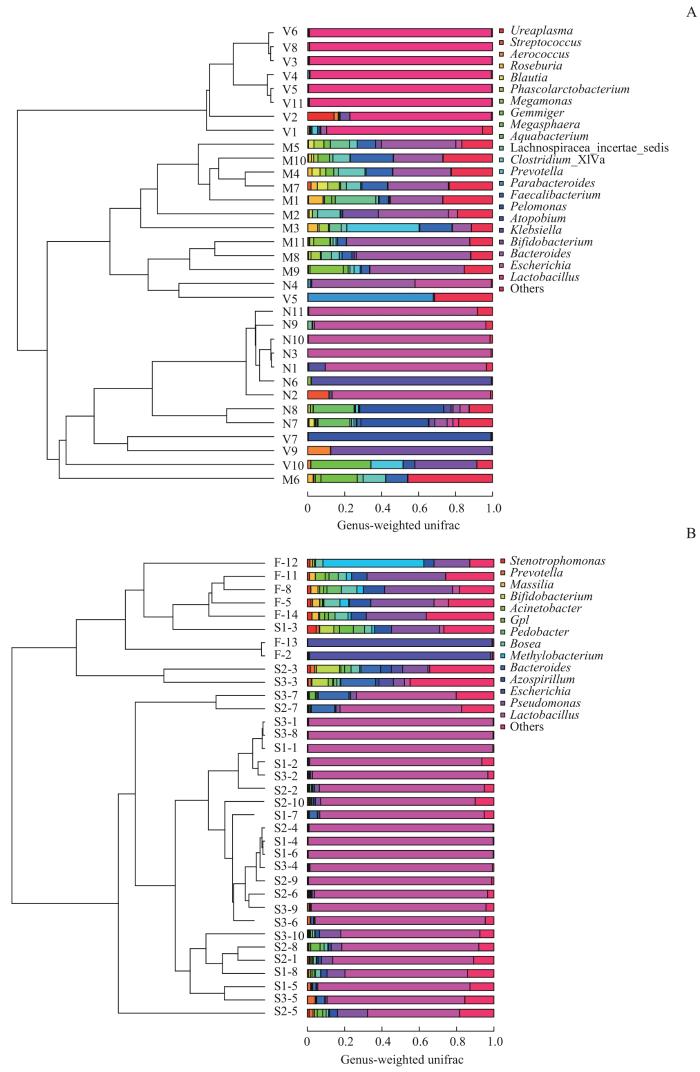

图9

图9

不同样本菌群UPGMA分析

Note: A. Maternal gut microbiota, and vaginal microbiota in late-pregnancy and neonatal meconium microbiota from the 11 pairs of mothers and newborns. B. Neonatal vernix caseosa (at forehead, axilla and inguinal crease) and meconium microbiota from the 14 newborns. M1‒M11: maternal gut microbiota; V1‒V11: maternal vaginal microbiota; N1‒N11: neonatal meconium microbiota; S1-1‒S1-8: neonatal vernix caseosa at forehead; S2-1‒S2-10: neonatal vernix caseosa at axilla; S3-1‒S3-10: neonatal vernix caseosa at inguinal crease; F-2, F-5, F-8, F-11‒F-14: neonatal meconium.

Fig 9

UPGMA analysis of the microbiota from different samples

3 讨论

本研究的婴儿均为阴道分娩、足月妊娠的正常新生儿。结果显示,孕妇孕晚期肠道菌群、阴道菌群与新生儿胎粪菌群、胎皮脂菌群有相关性,也存在差异,主要表现在菌群多样性和构成。母亲肠道菌群的α多样性高于阴道菌群和新生儿胎粪菌群;新生儿胎皮脂菌群α多样性高于胎粪菌群。母亲肠道菌群、阴道菌群和新生儿胎粪菌群OTU数量依次减少。门水平上,厚壁菌门在母亲孕晚期肠道菌群、阴道菌群及新生儿胎皮脂菌群中均为优势菌群。母亲孕晚期肠道菌群优势菌主要为厚壁菌门和拟杆菌门;阴道菌群优势菌为厚壁菌门。新生儿胎皮脂菌群的优势菌为厚壁菌门,3个部位(额部、腋窝、腹股沟)的胎皮脂菌群相似;而新生儿胎粪菌群的优势菌则为变形菌门。属水平上,母亲孕晚期肠道菌群的优势菌为拟杆菌属、栖粪杆菌属;阴道菌群的优势菌为乳杆菌属、双歧杆菌属;新生儿胎皮脂菌群的优势菌为乳杆菌属、假单胞菌属;新生儿胎粪菌群的优势菌则为埃希菌属。新生儿胎粪菌群与母亲肠道菌群和阴道菌群也具有相似性,均有埃希菌属、克雷伯菌属、拟杆菌属、乳杆菌属、双歧杆菌属等。乳杆菌属在母亲阴道菌群及新生儿胎皮脂菌群中均为优势菌属,提示可能与阴道分娩过程中胎儿皮肤(胎皮脂)接触母亲阴道菌群有关。

肠道菌群是一个非常复杂的微生物群落,在维持人体健康方面发挥着至关重要的作用[1]。新生儿肠道菌群的定植,为肠道正常发育和免疫系统成熟提供了必要的刺激,有助于建立适当的肠道稳态和黏膜屏障功能[13]。新生儿肠道菌群的定植开始于宫内还是出生后仍存争议。胎粪是新生儿出生后首次排出的墨绿色至黑色的黏液物质。它由肠腺的分泌物、胆汁色素、脂肪酸、羊水和宫内碎屑等组成[14]。因为胎粪形成于新生儿出生前,其微生物组成最可能反映胎儿在妊娠期宫内的微生物暴露情况。本研究在胎粪中检出微生物组,提示新生儿肠道菌群定植可能始于宫内,与近年来的研究[15-16]结果一致;我们以往的研究[17]也在胎盘中检测到微生物;健康非妊娠妇女的子宫内膜上也存在微生物[18]。但是也有研究[19-20]认为,健康胎儿宫内暴露于微生物的证据不足。所以对于此问题还需要更多的大样本研究进行验证。

本研究验证了微生物从母体向新生儿垂直传播的迹象:健康新生儿肠道微生物的早期定植,主要来自母亲的垂直传递以及环境暴露[25]。有研究[9]显示,胎儿肠道微生物可能来源于母亲的肠道、阴道、口腔、皮肤微生物等。首先,母亲肠道微生物可能是新生儿肠道微生物的来源。本研究在新生儿胎粪菌群中检测到广泛存在于人类肠道菌群中的埃希菌属、拟杆菌属等,验证了以往研究[21]的结果;动物实验[26]也发现,妊娠小鼠口服标记的屎肠球菌(Enterococcus faecium),小鼠子代的胎粪菌群中也检测到带标记的屎肠球菌,但对照组小鼠子代的胎粪菌群中没有检测到。目前母亲肠道微生物向胎儿肠道转移的机制尚未明确。其次,母亲阴道微生物也是新生儿肠道微生物的来源。本研究在新生儿胎粪菌群中检测到广泛存在于母亲阴道菌群的乳杆菌属,我们推测其来源于母亲阴道菌群。有研究[27]显示,新生儿胎粪菌群和母亲阴道菌群共享的序列数多于母亲肠道菌群和口腔菌群,表明新生儿胎粪菌群和母亲阴道菌群的相似性更高。母亲肠道菌群会诱导子代免疫系统的发育。有动物实验[28]发现,利用基因工程对怀孕雌鼠在肠道内进行短暂的大肠埃希菌HA107的定植(这种菌株在肠道中不会持续存在),其仔鼠出生后早期肠道固有白细胞的数量相比对照组增加。

胎皮脂是一种在妊娠晚期由胎儿皮脂腺和角质细胞合成、覆盖于胎儿皮肤表面、脂肪含量丰富的白色物质[12]。此前很多研究都关注成人皮肤微生物的组成[29],而对于新生儿胎皮脂的研究多集中在胎皮脂的组成[30]、功能[31]以及影响胎皮脂分布的因素[32]等方面,对新生儿胎皮脂微生物的研究很少。本研究发现,新生儿胎皮脂菌群丰富度高于胎粪菌群,可能是由于新生儿在分娩的过程中接触了母亲阴道菌群,且新生儿胎皮脂菌群以厚壁菌门、乳杆菌属为主,与母亲孕晚期阴道菌群相似。本研究新生儿3个部位胎皮脂微生物的组成相似,但额部胎皮脂乳杆菌科相对丰度高。我们推测,可能是因为在分娩过程中,新生儿的头部最先接触母亲阴道所致。我们认为,胎儿在子宫内,其腋窝常常被包裹在羊水中,更为湿润,所以棒杆菌科相对丰度较高。也有文献[33]显示,健康成人腋窝皮肤菌群棒杆菌属(Corynebacteria)的相对丰度较高。此外,由于身体各个部位的生理特点不尽相同,新生儿3个部位(额部、腋窝、腹股沟)的菌群组成存在一定的差异[34]。本研究分析了新生儿不同部位胎皮脂样本的微生物组成,可对未来进一步大样本研究的样本采集提供参考。

本研究存在一定的局限性。由于本研究仅对阴道分娩的母婴进行研究,且胎皮脂需由产科护士在胎儿娩出5 min内完成采样,有一定的难度。因此,样本采集采取了分段匹配,而非同一母婴连续完整样本。此外,本研究样本量相对较小,但本文所报告的研究结果均为稳定的结果和规律。例如菌群α多样性,母亲肠道菌群的OTU数、Ace指数、Chao1指数、Shannon指数均高于阴道菌群,后者高于新生儿胎粪菌群;新生儿额部和腹股沟部位的胎皮脂菌群的Ace指数和Chao1指数均高于胎粪菌群。从菌群构成的角度看,图5展示了母亲和婴儿菌群在门及属水平上的构成,不同种类样本间的区别明显,个体间差异相对较小。例如,母亲肠道菌群以厚壁菌门和拟杆菌门为主,相对丰度分别高达52.76%和41.67%;母亲阴道菌群厚壁菌门占主导地位,相对丰度高达74.36%;新生儿胎粪菌群都以变形菌门为优势菌门,相对丰度为80%以上;新生儿胎皮脂菌群以厚壁菌门占主导地位,为84.22%。本研究的数据支持上述母亲肠道菌群、阴道菌群、新生儿胎粪和胎皮脂菌群的多样性以及菌群构成特点的结果及结论。

本研究在阴道自然分娩的母婴中发现母亲肠道菌群、阴道菌群及胎粪菌群的α多样性依次降低,胎皮脂菌群又高于胎粪菌群。厚壁菌门在母亲肠道菌群、阴道菌群及新生儿胎皮脂菌群中均为优势菌群;乳杆菌属在阴道菌群及新生儿胎皮脂菌群中均为优势菌属,可能与阴道分娩过程中胎儿皮肤接触母亲阴道菌群有关。新生儿额部、腋窝、腹股沟的胎皮脂菌群相似,但有别于胎粪菌群。本研究提示阴道自然分娩母婴菌群的传递和特点,以及对早期菌群形成的可能影响。

作者贡献声明

欧阳凤秀负责研究的构思、设计和实施;马锦倩、欧阳凤秀负责论文撰写与修改;欧阳凤秀、范翩翩负责菌群检测和统计分析;范翩翩、郑涛、张琳、陈远志负责生物样本的采集;申剑参与了论文审阅与修改。所有作者均阅读并同意了最终稿件的提交。

AUTHOR's CONTRIBUTIONS

The study was conceived, designed, and implemented by OUYANG Fengxiu. The manuscript was drafted and revised by MA Jinqian and OUYANG Fengxiu. The microbiota analysis and statistical analysis were performed by OUYANG Fengxiu and FAN Pianpian. The bio-samples were collected by FAN Pianpian, ZHENG Tao, ZHANG Lin, and CHEN Yuanzhi. SHEN Jian reviewed and revised the manuscript. All the authors have read the last version of paper and consented for submission.

利益冲突声明

所有作者声明不存在利益冲突。

COMPETING INTERESTS

All authors disclose no relevant conflict of interests

All experimental protocols in this study were reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Xinhua Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (Approval Letter No. XHEC-C-2019-084), and consent letters have been signed by the pregnant women in the research.

参考文献