上海交通大学学报(医学版) ›› 2024, Vol. 44 ›› Issue (1): 50-63.doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-8115.2024.01.006

马锦倩1,2( ), 范翩翩1(

), 范翩翩1( ), 郑涛1,3, 张琳3,4, 陈远志1, 申剑5, 欧阳凤秀1,2(

), 郑涛1,3, 张琳3,4, 陈远志1, 申剑5, 欧阳凤秀1,2( )

)

收稿日期:2023-06-09

接受日期:2023-12-05

出版日期:2024-01-28

发布日期:2024-01-28

通讯作者:

欧阳凤秀,电子信箱:ouyangfengxiu@xinhuamed.com.cn。作者简介:马锦倩(1999—),女,硕士生;电子信箱:mjq18335988098@126.com基金资助:

MA Jinqian1,2( ), FAN Pianpian1(

), FAN Pianpian1( ), ZHENG Tao1,3, ZHANG Lin3,4, CHEN Yuanzhi1, SHEN Jian5, OUYANG Fengxiu1,2(

), ZHENG Tao1,3, ZHANG Lin3,4, CHEN Yuanzhi1, SHEN Jian5, OUYANG Fengxiu1,2( )

)

Received:2023-06-09

Accepted:2023-12-05

Online:2024-01-28

Published:2024-01-28

Contact:

OUYANG Fengxiu, E-mail: ouyangfengxiu@xinhuamed.com.cn.Supported by:摘要:

目的·分析母亲孕晚期肠道菌群、阴道菌群、新生儿胎粪及胎皮脂菌群的多样性及菌群构成,比较其异同及相关性。方法·前瞻性研究。招募2018年8月—11月于上海交通大学医学院附属新华医院分娩的11对母婴,采集母亲孕晚期粪便样本、阴道拭子及新生儿胎粪;招募2018年12月于上海交通大学医学院附属国际和平妇幼保健院分娩的14名新生儿,采集额部、腋窝、腹股沟部位的胎皮脂及胎粪样本。所有孕妇均为阴道自然分娩。采用16S rRNA基因V3~V4区测序进行微生物检测,分析11对母婴中母亲的肠道菌群、阴道菌群和新生儿的胎粪菌群,以及14名新生儿的胎皮脂菌群和胎粪菌群的多样性、菌群构成,分析异同及相关性。结果·母亲肠道菌群的操作分类单元(operational taxonomic unit,OTU)数、Ace指数、Chao1指数、Shannon指数均高于阴道菌群和新生儿胎粪菌群;新生儿3个部位胎皮脂菌群的Ace指数和Chao1指数均显著高于胎粪菌群(均P<0.01)。母亲肠道菌群、阴道菌群和新生儿胎粪菌群β多样性存在差异(P<0.01);新生儿额部、腋窝和腹股沟3个部位胎皮脂菌群的β多样性相似,但与胎粪菌群存在差异(P<0.01)。在门水平上,母亲肠道菌群优势菌主要为厚壁菌门(Firmicutes,52.76%)和拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes,41.67%),阴道菌群优势菌为厚壁菌门(74.36%)和放线菌门(Actinobacteria,21.25%),胎皮脂菌群的优势菌为厚壁菌门(84.22%)和变形菌门(Proteobacteria,8.80%),新生儿胎粪菌群在2个批次样本中优势菌均为变形菌门(分别占81.11%和88.72%)。在属水平上,母亲肠道菌群的优势菌为拟杆菌属(Bacteroides,35.42%)和栖粪杆菌属(Faecalibacterium,10.12%),阴道菌群的优势菌为乳杆菌属(Lactobacillus,69.10%)和双歧杆菌属(Bifidobacterium,11.30%),胎皮脂菌群的优势菌为乳杆菌属(79.81%)和假单胞菌属(Pseudomonas,3.23%),胎粪菌群的优势菌在2个批次样本中均为埃希菌属(Escherichia,分别占55.21%和31.18%)。结论·母亲孕晚期肠道菌群的α多样性高于阴道菌群和新生儿胎粪菌群,新生儿胎皮脂菌群α多样性高于胎粪菌群。厚壁菌门在母亲孕晚期肠道菌群、阴道菌群及新生儿胎皮脂菌群中均为优势菌,乳杆菌属在母亲阴道菌群及新生儿胎皮脂菌群中均为优势菌,胎粪菌群以变形菌门和埃希菌属较多。新生儿不同身体部位的胎皮脂菌群结构相似,但与胎粪菌群存在差异。

中图分类号:

马锦倩, 范翩翩, 郑涛, 张琳, 陈远志, 申剑, 欧阳凤秀. 孕妇肠道、阴道菌群和新生儿胎粪、胎皮脂菌群的相关性研究[J]. 上海交通大学学报(医学版), 2024, 44(1): 50-63.

MA Jinqian, FAN Pianpian, ZHENG Tao, ZHANG Lin, CHEN Yuanzhi, SHEN Jian, OUYANG Fengxiu. Relationship among maternal gut, vaginal microbiota and microbiota in meconium and vernix caseosa in newborns[J]. Journal of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (Medical Science), 2024, 44(1): 50-63.

| Characteristic | Value | Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristic (n=11) | Weight gain in mid to late pregnancy/kg | 12.69±4.50 | |

| Age/year | 29.00±4.03 | Gestational diabetes mellitus/n(%) | 1(9.1) |

| Education level/n(%) | GBS positive/n(%) | 0(0) | |

| High school or below | 3(27.3) | Puerperal fever/n(%) | 0(0) |

| College or above | 8(72.7) | Infant characteristic (n=11) | |

| Parity/n(%) | Infant gender/n(%) | ||

| 0 | 8(72.7) | Girl | 4(36.4) |

| ≥1 | 3(27.3) | Boy | 7(63.6) |

| Antibiotics use during child delivery/n(%) | Weight for gestational age/n(%) | ||

| No | 8(72.7) | SGA | 2(18.2) |

| Yes | 3(27.3) | AGA | 8(72.7) |

| Early pregnancy BMI/n(%) | LGA | 1(9.1) | |

| <18.5 kg·m-2 | 0(0) | Entering NICU after birth/n(%) | |

| 18.5‒23.9 kg·m-2 | 8(72.7) | Yes | 1 (9.1) |

| 24.0‒27.9 kg·m-2 | 1(9.1) | No | 10(90.9) |

| ≥28 kg·m-2 | 2(18.2) | Gestational age at birth/week | 40.18±0.75 |

| Pre-delivery BMI/n(%) | Length/cm | 50.27±1.62 | |

| <18.5 kg·m-2 | 0(0) | Birth weight/g | 3 536.36±423.66 |

| 18.5‒23.9 kg·m-2 | 0(0) | Head circumference/cm | 34.55±1.21 |

| 24.0‒27.9 kg·m-2 | 6(54.5) | Birth BMI/(kg·m-2) | 13.96±1.15 |

| ≥28 kg·m-2 | 5(45.5) | Neonatal antibiotics use/n(%) | 0(0) |

表1 11对母婴的临床特征

Tab 1 Clinical characteristics of 11 pairs of mothers and newborns

| Characteristic | Value | Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristic (n=11) | Weight gain in mid to late pregnancy/kg | 12.69±4.50 | |

| Age/year | 29.00±4.03 | Gestational diabetes mellitus/n(%) | 1(9.1) |

| Education level/n(%) | GBS positive/n(%) | 0(0) | |

| High school or below | 3(27.3) | Puerperal fever/n(%) | 0(0) |

| College or above | 8(72.7) | Infant characteristic (n=11) | |

| Parity/n(%) | Infant gender/n(%) | ||

| 0 | 8(72.7) | Girl | 4(36.4) |

| ≥1 | 3(27.3) | Boy | 7(63.6) |

| Antibiotics use during child delivery/n(%) | Weight for gestational age/n(%) | ||

| No | 8(72.7) | SGA | 2(18.2) |

| Yes | 3(27.3) | AGA | 8(72.7) |

| Early pregnancy BMI/n(%) | LGA | 1(9.1) | |

| <18.5 kg·m-2 | 0(0) | Entering NICU after birth/n(%) | |

| 18.5‒23.9 kg·m-2 | 8(72.7) | Yes | 1 (9.1) |

| 24.0‒27.9 kg·m-2 | 1(9.1) | No | 10(90.9) |

| ≥28 kg·m-2 | 2(18.2) | Gestational age at birth/week | 40.18±0.75 |

| Pre-delivery BMI/n(%) | Length/cm | 50.27±1.62 | |

| <18.5 kg·m-2 | 0(0) | Birth weight/g | 3 536.36±423.66 |

| 18.5‒23.9 kg·m-2 | 0(0) | Head circumference/cm | 34.55±1.21 |

| 24.0‒27.9 kg·m-2 | 6(54.5) | Birth BMI/(kg·m-2) | 13.96±1.15 |

| ≥28 kg·m-2 | 5(45.5) | Neonatal antibiotics use/n(%) | 0(0) |

| Characteristic | Value | Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristic (n=14) | Weight gain in mid to late pregnancy/kg | 11.09±9.63 | |

| Age/year | 30.43±2.90 | Gestational diabetes mellitus/n(%) | 1(7.1) |

| Education level/n(%) | GBS positive/n(%) | 0(0) | |

| High school or below | 3(21.4) | Puerperal fever/n(%) | 0(0) |

| College or above | 11(78.6) | Infant characteristic (n=14) | |

| Parity/n(%) | Infant gender/n(%) | ||

| 0 | 10(71.4) | Girl | 7(50.0) |

| ≥1 | 4(28.6) | Boy | 7(50.0) |

| Antibiotics use during child delivery/n(%) | Weight for gestational age/n(%) | ||

| No | 11(78.57) | SGA | 0(0) |

| Yes | 3(21.43) | AGA | 10(71.4) |

| Early pregnancy BMI/n(%) | LGA | 4(28.6) | |

| <18.5 kg·m-2 | 0(0) | Entering NICU after birth/n(%) | |

| 18.5‒23.9 kg·m-2 | 11(78.6) | Yes | 2(14.3) |

| 24.0‒27.9 kg·m-2 | 2(14.3) | No | 12(85.7) |

| ≥28 kg·m-2 | 1(7.1) | Gestational age at birth/week | 39.14±0.95 |

| Pre-delivery BMI/n(%) | Length/cm | 50.00±0.88 | |

| <18.5 kg·m-2 | 0(0) | Birth weight/g | 3 418.93±371.51 |

| 18.5‒23.9 kg·m-2 | 2(14.3) | Birth BMI/(kg·m-2) | 13.66±1.26 |

| 24.0‒27.9 kg·m-2 | 8(57.1) | Neonatal antibiotics use/n(%) | 0(0) |

| ≥28 kg·m-2 | 4(28.6) | - | - |

表2 14名新生儿及其母亲的临床特征

Tab 2 Clinical characteristics of 14 newborns and their mothers

| Characteristic | Value | Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristic (n=14) | Weight gain in mid to late pregnancy/kg | 11.09±9.63 | |

| Age/year | 30.43±2.90 | Gestational diabetes mellitus/n(%) | 1(7.1) |

| Education level/n(%) | GBS positive/n(%) | 0(0) | |

| High school or below | 3(21.4) | Puerperal fever/n(%) | 0(0) |

| College or above | 11(78.6) | Infant characteristic (n=14) | |

| Parity/n(%) | Infant gender/n(%) | ||

| 0 | 10(71.4) | Girl | 7(50.0) |

| ≥1 | 4(28.6) | Boy | 7(50.0) |

| Antibiotics use during child delivery/n(%) | Weight for gestational age/n(%) | ||

| No | 11(78.57) | SGA | 0(0) |

| Yes | 3(21.43) | AGA | 10(71.4) |

| Early pregnancy BMI/n(%) | LGA | 4(28.6) | |

| <18.5 kg·m-2 | 0(0) | Entering NICU after birth/n(%) | |

| 18.5‒23.9 kg·m-2 | 11(78.6) | Yes | 2(14.3) |

| 24.0‒27.9 kg·m-2 | 2(14.3) | No | 12(85.7) |

| ≥28 kg·m-2 | 1(7.1) | Gestational age at birth/week | 39.14±0.95 |

| Pre-delivery BMI/n(%) | Length/cm | 50.00±0.88 | |

| <18.5 kg·m-2 | 0(0) | Birth weight/g | 3 418.93±371.51 |

| 18.5‒23.9 kg·m-2 | 2(14.3) | Birth BMI/(kg·m-2) | 13.66±1.26 |

| 24.0‒27.9 kg·m-2 | 8(57.1) | Neonatal antibiotics use/n(%) | 0(0) |

| ≥28 kg·m-2 | 4(28.6) | - | - |

图1 不同样本OTU数量的Venn图Note: A. Maternal gut microbiota, and vaginal microbiota in late-pregnancy and neonatal meconium microbiota from the 11 pairs of mothers and newborns. B. Neonatal vernix caseosa (at forehead, axilla, and inguinal crease) and meconium microbiota from the 14 newborns.

Fig 1 Venn diagrams of the OTU numbers from different samples

图2 母亲孕晚期肠道菌群、阴道菌群和新生儿胎粪菌群Ace (A), Chao1 (B), Shannon (C)及Simpson (D)指数箱型图Note: M—maternal gut microbiota; V—maternal vaginal microbiota; N—neonatal meconium microbiota.

Fig 2 Box plots of Ace (A), Chao1 (B), Shannon (C), and Simpson (D) indices of maternal gut microbiota and vaginal microbiota in late-pregnancy and neonatal meconium microbiota

图3 新生儿胎皮脂菌群和胎粪菌群Ace (A), Chao1 (B), Shannon (C)及Simpson (D)指数箱型图Note: S1—neonatal vernix caseosa at forehead; S2—neonatal vernix caseosa at axilla; S3—neonatal vernix caseosa at inguinal crease; F—neonatal meconium.

Fig 3 Box plots of Ace (A), Chao1 (B), Shannon (C), and Simpson (D) indices of microbiota in neonatal vernix caseosa and meconium

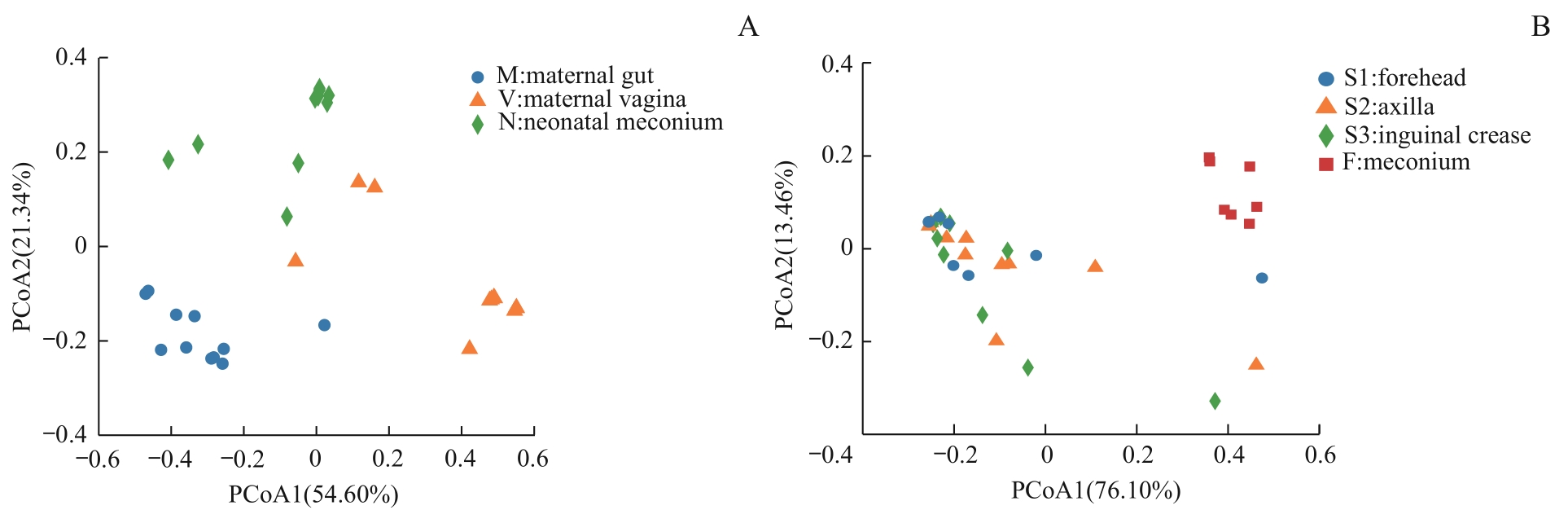

图4 不同样本菌群β多样性PCoA分析Note: A. Maternal gut microbiota and vaginal microbiota in late-pregnancy and neonatal meconium microbiota from the 11 pairs of mothers and newborns. B. Neonatal vernix caseosa (at forehead, axilla, and inguinal crease) and meconium microbiota from the 14 newborns.

Fig 4 PCoA analysis of β diversity of the microbiota from different samples

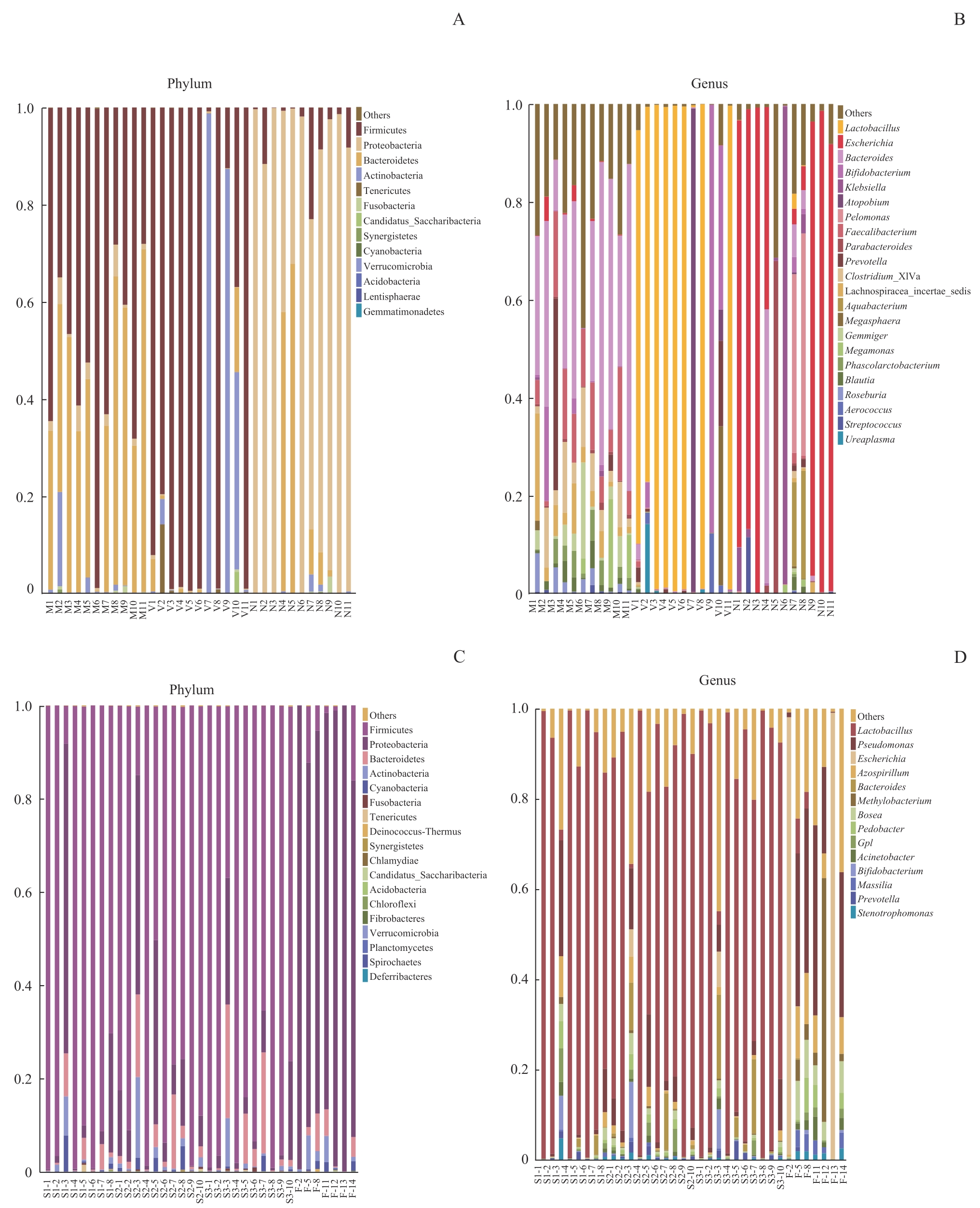

图5 不同样本菌群门和属水平物种相对丰度柱形图Note: A/B. Maternal gut microbiota and vaginal microbiota in late-pregnancy and neonatal meconium microbiota from the 11 pairs of mothers and newborns at the levels of phylum (A) and genus (B). C/D. Neonatal vernix caseosa (at forehead, axilla, and inguinal crease) and meconium microbiota from the 14 newborns at the levels of phylum (C) and genus (D). M1?M11: maternal gut microbiota; V1?V11: maternal vaginal microbiota; N1?N11: neonatal meconium microbiota; S1-1?S1-8: neonatal vernix caseosa at forehead; S2-1?S2-10: neonatal vernix caseosa at axilla; S3-1?S3-10: neonatal vernix caseosa at inguinal crease; F-2, F-5, F-8, F-11?F-14: neonatal meconium.

Fig 5 Histogram of relative species abundance at the phylum and genus levels in different samples

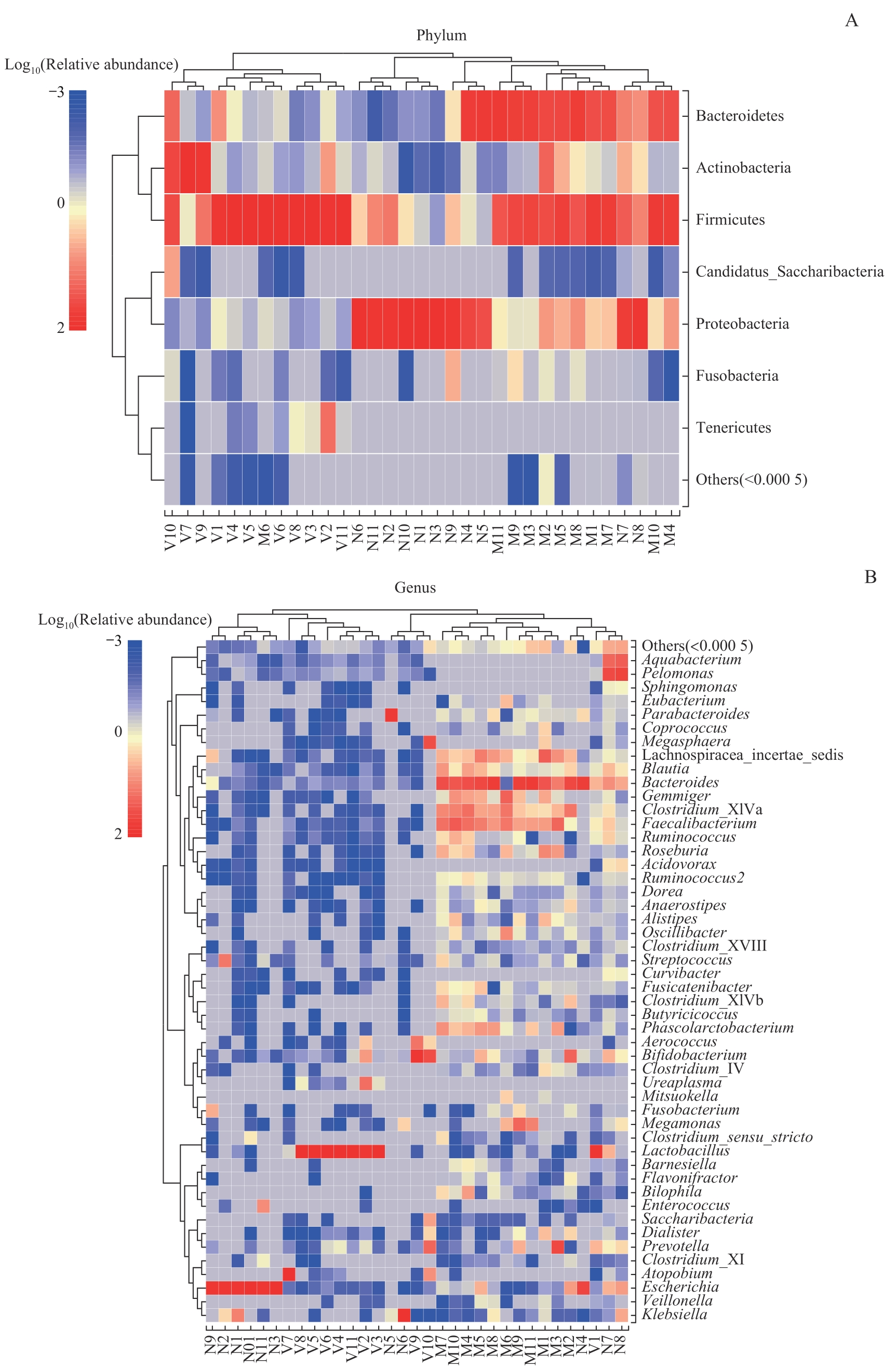

图6 母亲孕晚期肠道菌群、阴道菌群、新生儿胎粪菌群门(A)和属(B)水平物种组成热图Note: Due to the potential significant differences in relative abundance of species, sample clustering was affected. After multiplying the relative abundance by 100, a log transformation with a base of 10 was performed [y=lg(100x)]. If the relative abundance of species in the sample was 0, it would be replaced with the log value of half of the minimum value (≠0) of species abundance in all samples.

Fig 6 Species composition heatmaps at the level of phylum (A) and genus (B) in the maternal gut microbiota and maternal vaginal microbiota in late-pregnancy and neonatal meconium microbiota

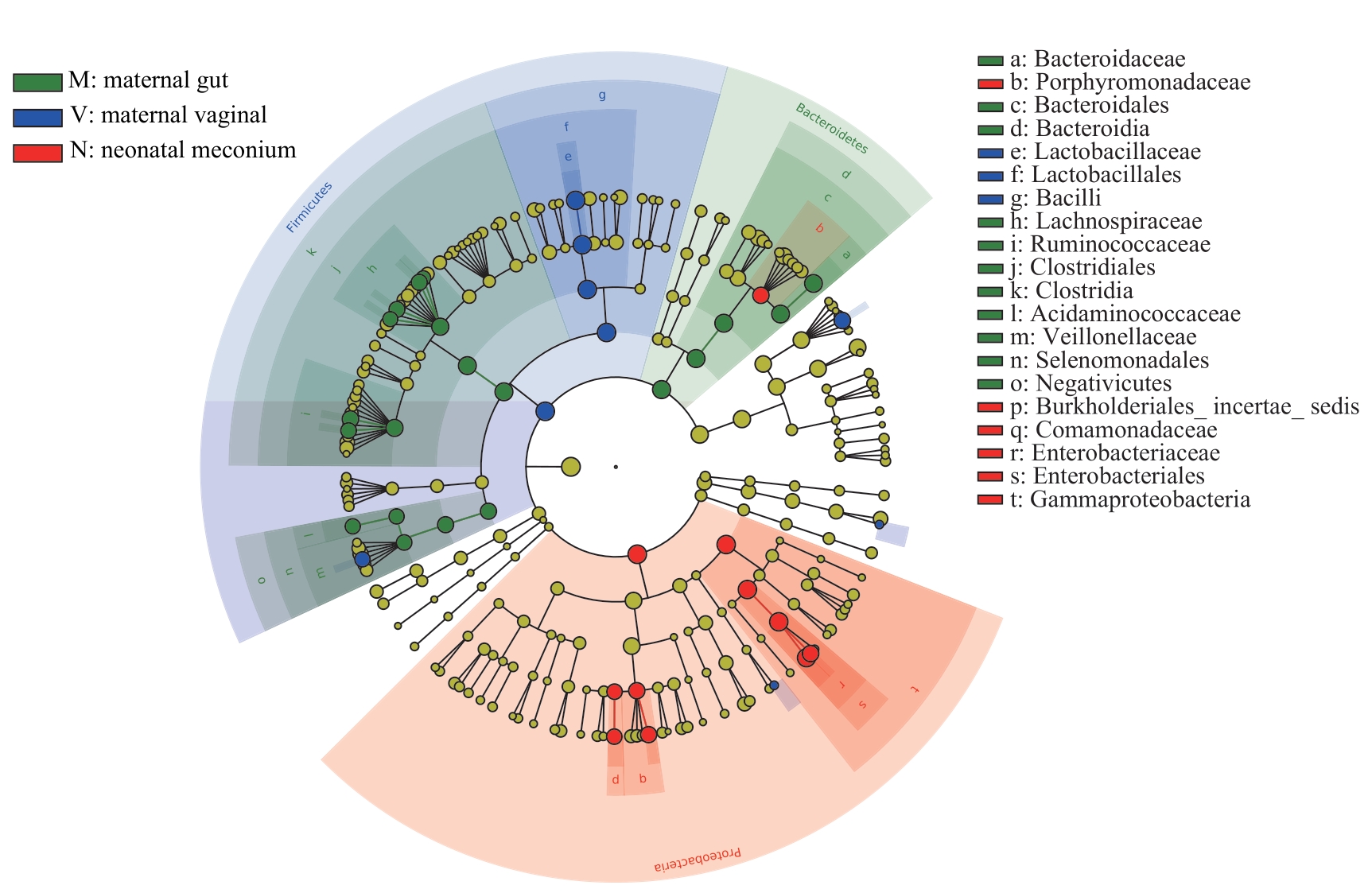

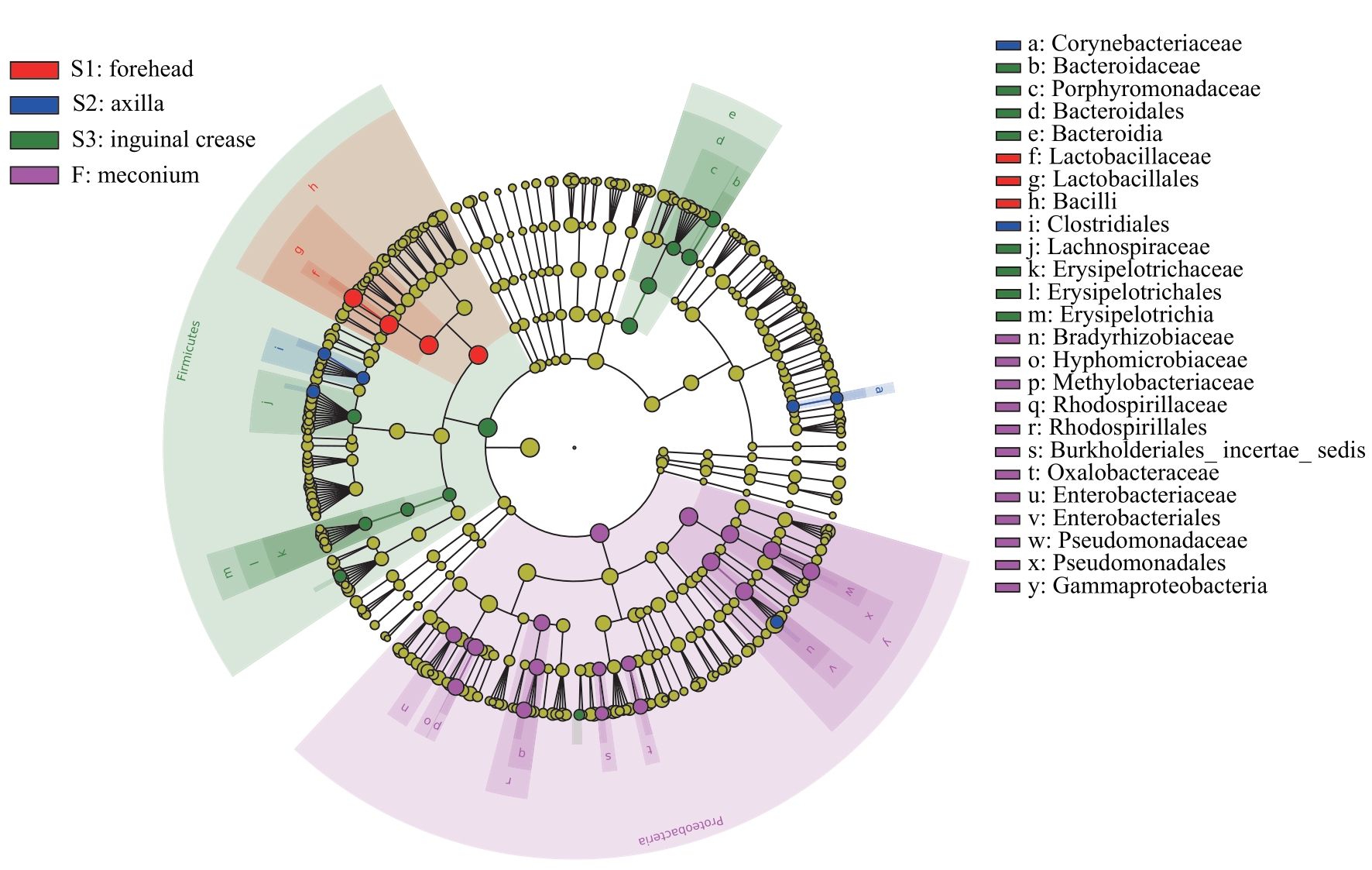

图7 母亲孕晚期肠道菌群、阴道菌群和新生儿胎粪菌群LEfSe分析进化分支图Note: Different colors in the figure represent different microbial communities. The yellow nodes represent microbial communities that do not play an important role in the 3 groups. The green nodes represent microbial communities that play an important role in the maternal gut microbiota. The blue nodes represent microbial communities that play an important role in the maternal vaginal microbiota. The red nodes represent microbial communities that play an important role in the neonatal meconium microbiota. From the inside out, each circle consists of species at the level of phylum, class, order, family, and genus.

Fig 7 LEfSe cladogram of analysis on the maternal gut microbiota, and vaginal microbiota in late-pregnancy and neonatal meconium microbiota

图8 新生儿胎皮脂菌群和胎粪菌群LEfSe分析进化分支图Note: The red nodes represent the microbial communities that play an important role in the neonatal vernix caseosa at forehead. The blue nodes represent the microbial communities that play an important role in the neonatal vernix caseosa at axilla. The green nodes represent the microbial communities that play an important role in the neonatal vernix caseosa at inguinal crease. The purple nodes represent the microbial communities that play an important role in neonatal meconium. From the inside out, each circle consists of species at the level of phylum, class, order, family, and genus.

Fig 8 LEfSe cladogram of analysis of the neonatal vernix caseosa microbiota and meconium microbiota

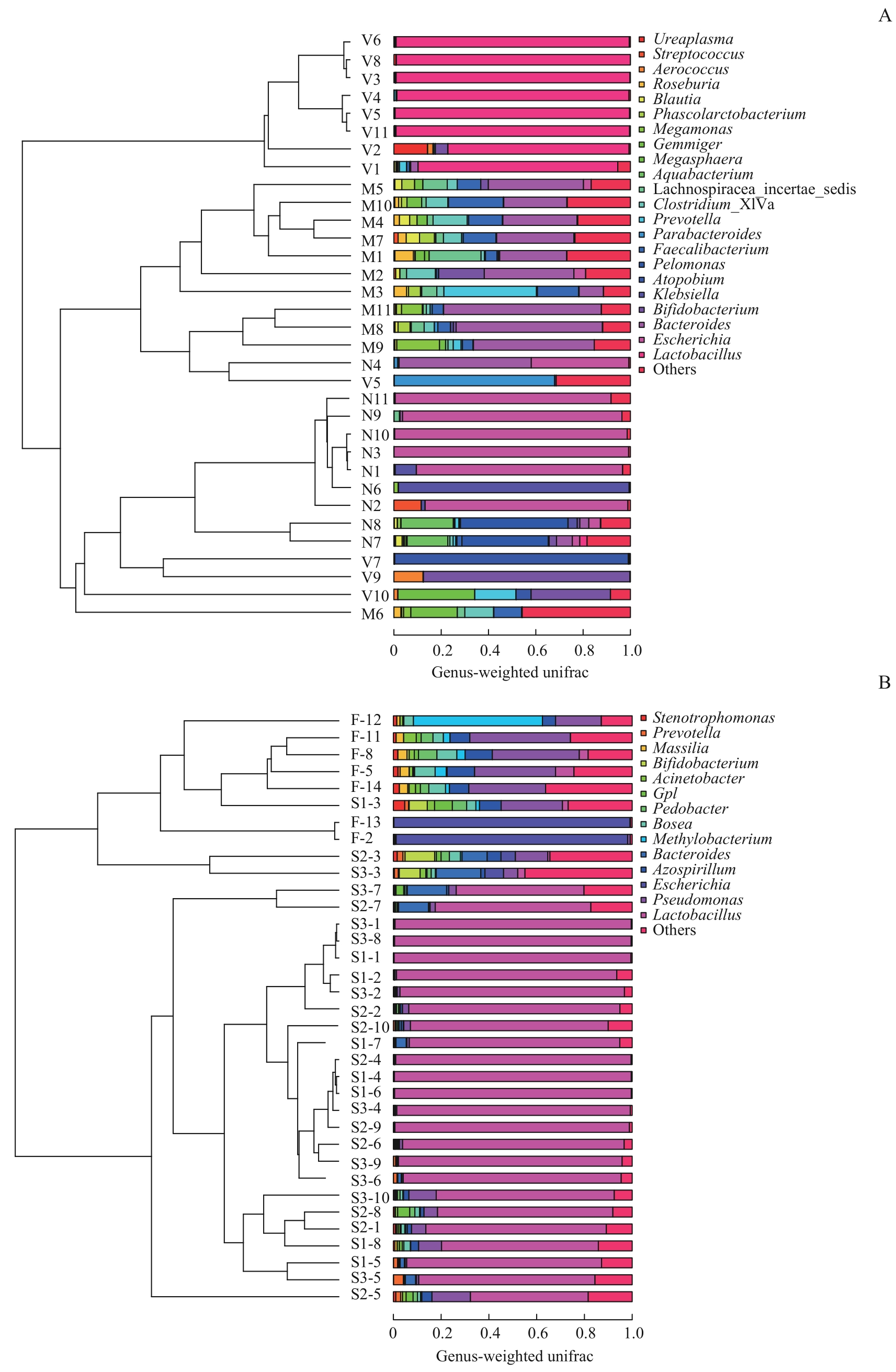

图9 不同样本菌群UPGMA分析Note: A. Maternal gut microbiota, and vaginal microbiota in late-pregnancy and neonatal meconium microbiota from the 11 pairs of mothers and newborns. B. Neonatal vernix caseosa (at forehead, axilla and inguinal crease) and meconium microbiota from the 14 newborns. M1?M11: maternal gut microbiota; V1?V11: maternal vaginal microbiota; N1?N11: neonatal meconium microbiota; S1-1?S1-8: neonatal vernix caseosa at forehead; S2-1?S2-10: neonatal vernix caseosa at axilla; S3-1?S3-10: neonatal vernix caseosa at inguinal crease; F-2, F-5, F-8, F-11?F-14: neonatal meconium.

Fig 9 UPGMA analysis of the microbiota from different samples

| 1 | LI D T, WANG P, WANG P P, et al. The gut microbiota: a treasure for human health[J]. Biotechnol Adv, 2016, 34(7): 1210-1224. |

| 2 | WAMPACH L, HEINTZ-BUSCHART A, FRITZ J V, et al. Birth mode is associated with earliest strain-conferred gut microbiome functions and immunostimulatory potential[J]. Nat Commun, 2018, 9(1): 5091. |

| 3 | ARRIETA M C, ARÉVALO A, STIEMSMA L, et al. Associations between infant fungal and bacterial dysbiosis and childhood atopic wheeze in a nonindustrialized setting[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2018, 142(2): 424-434.e10. |

| 4 | RAUTAVA S, LUOTO R, SALMINEN S, et al. Microbial contact during pregnancy, intestinal colonization and human disease[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2012, 9(10): 565-576. |

| 5 | KRONMAN M P, ZAOUTIS T E, HAYNES K, et al. Antibiotic exposure and IBD development among children: a population-based cohort study[J]. Pediatrics, 2012, 130(4): e794-e803. |

| 6 | STOUT M J, CONLON B, LANDEAU M, et al. Identification of intracellular bacteria in the basal plate of the human placenta in term and preterm gestations[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2013, 208(3): 226.e1-226.e7. |

| 7 | MOREIRA L B, SILVA C B D, GERALDO-MARTINS V R, et al. Presence of Streptococcus mutans and interleukin-6 and -10 in amniotic fluid[J]. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med, 2022, 35(25): 9463-9469. |

| 8 | WITT R G, BLAIR L, FRASCOLI M, et al. Detection of microbial cell-free DNA in maternal and umbilical cord plasma in patients with chorioamnionitis using next generation sequencing[J]. PLoS One, 2020, 15(4): e0231239. |

| 9 | MAKINO H, KUSHIRO A, ISHIKAWA E, et al. Mother-to-infant transmission of intestinal bifidobacterial strains has an impact on the early development of vaginally delivered infant's microbiota[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(11): e78331. |

| 10 | ARBOLEYA S, SÁNCHEZ B, MILANI C, et al. Intestinal microbiota development in preterm neonates and effect of perinatal antibiotics[J]. J Pediatr, 2015, 166(3): 538-544. |

| 11 | FALLANI M, YOUNG D, SCOTT J, et al. Intestinal microbiota of 6-week-old infants across Europe: geographic influence beyond delivery mode, breast-feeding, and antibiotics[J]. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 2010, 51(1): 77-84. |

| 12 | VISSCHER M O, NARENDRAN V, PICKENS W L, et al. Vernix caseosa in neonatal adaptation[J]. J Perinatol, 2005, 25(7): 440-446. |

| 13 | ECHARRI P P, GRACIÁ C M, BERRUEZO G R, et al. Assessment of intestinal microbiota of full-term breast-fed infants from two different geographical locations[J]. Early Hum Dev, 2011, 87(7): 511-513. |

| 14 | TAPIAINEN T, PAALANNE N, TEJESVI M V, et al. Maternal influence on the fetal microbiome in a population-based study of the first-pass meconium[J]. Pediatr Res, 2018, 84(3): 371-379. |

| 15 | STINSON L F, BOYCE M C, PAYNE M S, et al. The not-so-sterile womb: evidence that the human fetus is exposed to bacteria prior to birth[J]. Front Microbiol, 2019, 10: 1124. |

| 16 | KLOPP J, FERRETTI P, MEYER C U, et al. Meconium microbiome of very preterm infants across Germany[J]. mSphere, 2022, 7(1): e0080821. |

| 17 | TANG N, LUO Z C, ZHANG L, et al. The association between gestational diabetes and microbiota in placenta and cord blood[J]. Front Endocrinol, 2020, 11: 550319. |

| 18 | MITCHELL C M, HAICK A, NKWOPARA E, et al. Colonization of the upper genital tract by vaginal bacterial species in nonpregnant women[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2015, 212(5): 611.e1-611.e9. |

| 19 | THEIS K R, ROMERO R, WINTERS A D, et al. Does the human placenta delivered at term have a microbiota? Results of cultivation, quantitative real-time PCR, 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and metagenomics[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2019, 220(3): 267.e1-267.e39. |

| 20 | STERPU I, FRANSSON E, HUGERTH L W, et al. No evidence for a placental microbiome in human pregnancies at term[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2021, 224(3): 296.e1-296.e23. |

| 21 | FERRETTI P, PASOLLI E, TETT A, et al. Mother-to-infant microbial transmission from different body sites shapes the developing infant gut microbiome[J]. Cell Host Microbe, 2018, 24(1): 133-145.e5. |

| 22 | ROBERTSON R C, MANGES A R, FINLAY B B, et al. The human microbiome and child growth: first 1000 days and beyond[J]. Trends Microbiol, 2019, 27(2): 131-147. |

| 23 | WAMPACH L, HEINTZ-BUSCHART A, HOGAN A, et al. Colonization and succession within the human gut microbiome by Archaea, bacteria, and microeukaryotes during the first year of life[J]. Front Microbiol, 2017, 8: 738. |

| 24 | MILLER J L, SONIES B C, MACEDONIA C. Emergence of oropharyngeal, laryngeal and swallowing activity in the developing fetal upper aerodigestive tract: an ultrasound evaluation[J]. Early Hum Dev, 2003, 71(1): 61-87. |

| 25 | MILANI C, DURANTI S, BOTTACINI F, et al. The first microbial colonizers of the human gut: composition, activities, and health implications of the infant gut microbiota[J]. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev, 2017, 81(4): e00036-e00017. |

| 26 | JIMÉNEZ E, FERNÁNDEZ L, MARÍN M L, et al. Isolation of commensal bacteria from umbilical cord blood of healthy neonates born by cesarean section[J]. Curr Microbiol, 2005, 51(4): 270-274. |

| 27 | LIU C J, LIANG X, NIU Z Y, et al. Is the delivery mode a critical factor for the microbial communities in the meconium?[J]. EBioMedicine, 2019, 49: 354-363. |

| 28 | GOMEZ DE AGÜERO M, GANAL-VONARBURG S C, FUHRER T, et al. The maternal microbiota drives early postnatal innate immune development[J]. Science, 2016, 351(6279): 1296-1302. |

| 29 | FERČEK I, LUGOVIĆ-MIHIĆ L, TAMBIĆ-ANDRAŠEVIĆ A, et al. Features of the skin microbiota in common inflammatory skin diseases[J]. Life, 2021, 11(9): 962. |

| 30 | TAÏEB A. Skin barrier in the neonate[J]. Pediatr Dermatol, 2018, 35(Suppl 1): s5-s9. |

| 31 | NISHIJIMA K, YONEDA M, HIRAI T, et al. Biology of the vernix caseosa: a review[J]. J Obstet Gynaecol Res, 2019, 45(11): 2145-2149. |

| 32 | MESFIN S, AFEWORK M, BIKILA D, et al. Distribution of vernix caseosa and associated factors among newborns delivered at Adama Comprehensive Specialized Hospital Medical College, Ethiopia, in 2022: cross-sectional study[J]. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol, 2022, 15: 2903-2914. |

| 33 | GRICE E A, KONG H H, CONLAN S, et al. Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome[J]. Science, 2009, 324(5931): 1190-1192. |

| 34 | KONG H H. Skin microbiome: genomics-based insights into the diversity and role of skin microbes[J]. Trends Mol Med, 2011, 17(6): 320-328. |

| [1] | 李俊鹤, 张瑞, 刘庆旭, 随素敏. NR3C2基因变异致新生儿假性醛固酮减少症1例报道[J]. 上海交通大学学报(医学版), 2025, 45(7): 934-938. |

| [2] | 陈深册, 陈依明, 王凡, 张梦珂, 杨惟杰, 吕洞宾, 洪武. 饮食干预治疗抑郁相关症状的研究进展[J]. 上海交通大学学报(医学版), 2024, 44(8): 1050-1055. |

| [3] | 夏西茜, 丁珂珂, 张慧恒, 彭旭飞, 孙昳旻, 唐雅珺, 汤晓芳. 肠道菌群介导胆汁酸影响炎症性肠病的研究进展[J]. 上海交通大学学报(医学版), 2024, 44(7): 839-846. |

| [4] | 杜亚格, 卢言慧, 安宇, 宋颖, 郑婕. 肠道菌群在糖尿病认知功能障碍中的作用机制及靶向干预的研究进展[J]. 上海交通大学学报(医学版), 2024, 44(4): 494-500. |

| [5] | 李郡如, 欧阳彦, 谢静远. 肠道菌群在IgA肾病发病与治疗中的作用研究进展[J]. 上海交通大学学报(医学版), 2023, 43(8): 1044-1048. |

| [6] | 高羽, 殷姗, 庞玥, 梁文懿, 刘玉敏. 大黄对大鼠体内肠道菌群-宿主共代谢作用的影响[J]. 上海交通大学学报(医学版), 2023, 43(8): 997-1007. |

| [7] | 温亚锦, 何雯, 韩晓, 张晓波. 不同严重程度支气管哮喘儿童肠道菌群差异的探索性分析[J]. 上海交通大学学报(医学版), 2023, 43(6): 655-664. |

| [8] | 王洁仪, 郑丹, 郑晓皎, 贾伟, 赵爱华. 茶褐素生物学活性及其作用机制的研究进展[J]. 上海交通大学学报(医学版), 2023, 43(6): 768-774. |

| [9] | 刘芊若, 方子晨, 吴宇涵, 钟羡欣, 国沐禾, 贾洁. 肠道菌群及其代谢产物与妊娠期糖尿病相关性的研究进展[J]. 上海交通大学学报(医学版), 2023, 43(5): 641-647. |

| [10] | 张越, 瞿蕾, 谷沁, 朱亦清, 马莉莹, 孙文广. 妊娠期糖尿病孕妇尿酮体持续阳性对母婴临床结局的影响[J]. 上海交通大学学报(医学版), 2023, 43(3): 314-319. |

| [11] | 李雪, 肖伊, 张弘. 宫颈功能不全患者阴道菌群的分布特征及妊娠结局[J]. 上海交通大学学报(医学版), 2023, 43(11): 1417-1422. |

| [12] | 王婕, 吴慧, 卢凌鹏, 杨科峰, 祝捷, 周恒益, 姚蝶, 高雅, 冯宇婷, 刘玉红, 贾洁. 妊娠期糖尿病女性肠道菌群的变化特征及其与血糖、血脂和膳食的相关性[J]. 上海交通大学学报(医学版), 2022, 42(9): 1336-1346. |

| [13] | 卢雨, 王昊, 巴乾. 肠道菌群在肝癌发生发展及治疗中的作用研究进展[J]. 上海交通大学学报(医学版), 2022, 42(7): 939-944. |

| [14] | 李雅慧, 王依闻, 谢利娟. SAMD9基因新发突变引起新生儿MIRAGE综合征1例[J]. 上海交通大学学报(医学版), 2022, 42(11): 1644-1648. |

| [15] | 蒋怡, 江平, 张明明, 房静远. 嗜黏蛋白阿克曼菌在肠道相关疾病中作用的研究进展[J]. 上海交通大学学报(医学版), 2022, 42(10): 1490-1497. |

| 阅读次数 | ||||||

|

全文 |

|

|||||

|

摘要 |

|

|||||